Fila & Martin Mulligan: A Story That Deserves To Be Told

Fila is well-nigh the most recognisable brand of sportswear and accessories the world over, and a brand favoured by many tennis greats. Throughout the 1970s, considered to be the golden age of tennis, five-time Wimbledon champion Björn Borg famously donned Fila as his ruled the courts — and joining him were the likes of Adriano Panatta, Paolo Bertolucci, Evonne Goolagong, Guillermo Vilas. These are but a handful of mighty accomplishments for a company which had a humble beginning in 1911, primarily making underwear for the people of Biella and surrounding townships located near the foothills of the Italian Alps.

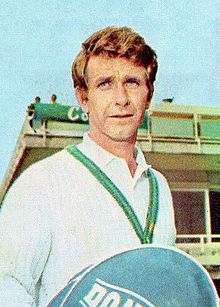

But another of Fila’s accomplishments, one that is perhaps lesser known though no less mighty, was the recruitment of Martin Mulligan into its ranks. No, Mulligan was not among the top players of the 1970s. His years of glory were during the 1960s, quite a few years before Fila entered the world of tennis in 1973. But as far as we are able to gather, the story of Fila would be carelessly incomplete if it did not include the story of Australian tennis player Martin Mulligan.

But another of Fila’s accomplishments, one that is perhaps lesser known though no less mighty, was the recruitment of Martin Mulligan into its ranks. No, Mulligan was not among the top players of the 1970s. His years of glory were during the 1960s, quite a few years before Fila entered the world of tennis in 1973. But as far as we are able to gather, the story of Fila would be carelessly incomplete if it did not include the story of Australian tennis player Martin Mulligan.

Mulligan, who was ranked five times in the World Top Ten, is best remembered for having won the Italian Open three times — beating Boro Jovanovic in ’63, Manuel Santana in ’65 and fellow Australian Tony Roche in ’67 — and for reaching the finals at Wimbledon in ’62, losing to Rod Laver, another fellow Australian.

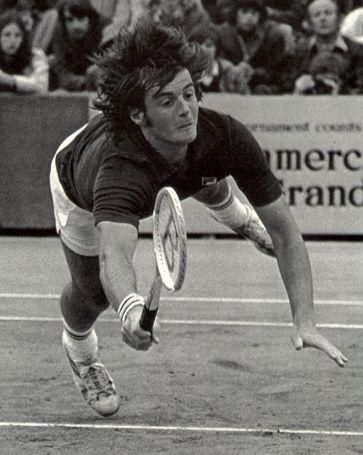

To continue the story of Fila and Mulligan it’s worth recalling for a moment the 1977 Davis Cup at White City Stadium in Sydney, in particular the finals match between Australia’s John Alexander and Italy’s Adriano Panatta. Neither player expected an easy win. Alexander had beaten Panatta in their last two encounters, at the Rotterdam Open earlier in the year and in the first round of the 1976 Davis Cup in Chile. Behind him, too, was the long history of Australia’s dominance in the Cup, second only to the United States at that time — a psychological advantage, if nothing else. Even so, Panatta only the year before had defeated Vilas in the final of the Italian Open, knocked out the indefatigable Borg in the quarterfinals of the French Open to then go on to take that title, and, though he lost to Alexander in Chile, had helped secure Italy’s first–ever Davis Cup victory when he beat both Patricio Cornejo and Jaime Fillol in the finals.

The match between Alexander and Panatta was a four-hour marathon, intensely fought, particularly in the fifth set, and, according to Mulligan, was a “hugely important match off the court as much as on.” That is, because a good many of the spectators belonged to a generation of Australians born of Italian parents who had immigrated to Australia in the 1950s.

Broadly speaking, spectators of a Davis Cup final should fall into two distinct camps — each camp respectively championing their own national players. But here was a generation of Australian-Italians who found themselves conflicted: to side with Panatta was almost to betray your country of birth; to side with Alexander was somehow to deny your Italian roots.

Mulligan well understands what it feels like to have divided loyalties. He was in attendance at White City Stadium in 1977, but not only as a representative of Fila, with whom he had been working for several years, oddly enough he was also coach of the Italian Davis Cup team, a position he held for 10 years from 1969 to 1979. Stranger still is that Mulligan, along with the great Nicola Pietrangeli, represented Italy in the 1968 Davis Cup.

Unlike today, back in the early 1960s the rewards on the tennis circuit in Australia were few and far between. The Lawn Tennis Association of Australia (now Tennis Australia) prohibited amateur players from the leaving the country before March to play in tournaments where money was, let’s say, more liberally available. “The Association banned Ken Fletcher, Bob Hewitt, Roy Emerson, Fred Stolle and myself because we all believed we were in the right,” explains Mulligan. “We were all in it together, but then Emerson and Stolle eventually went back and were kind of forgiven. The other three of us were not and we were left out on a limb, and so we decided separately to follow different paths. Fletcher went to Hong Kong, Hewitt went to South Africa, and I went to live in Italy.”

Tennis was Mulligan’s passport. He had lived in Italy for more than three years when in 1967 there was a move to have him play Davis Cup for Italy. As Mulligan goes on to explain, “There was a rule back then, which has since changed, that said if you lived in another country and had not played for your country of birth for several years, then you were eligible to represent your host country in Davis Cup competitions.” The Italian Tennis Federation refused at first believing that as an Australian his presence in the Italian team would draw adverse criticism. But given that Italy’s Davis Cup fortunes had been consistently dire over the three years prior, the federation reversed its decision and Mulligan was allowed into the team. (A coincidental footnote to this story of Italy’s dash for the 1968 Davis Cup is that in the quarterfinals of the European Draw, Italy defeated Monaco in Biella, the birthplace of Fila.)

Seven years ago Mulligan was the first non-Italian to be awarded the Golden Racquet from the Italian Tennis Federation in recognition of his contribution to tennis in general. Mulligan admits, however, that in having represented Italy in ’68, and indeed Italy having won the Cup in ’76 during his tenure as coach of the Italian Davis Cup team, likely contributed to his receiving the award. But it was Fila many years earlier that first recognised Mulligan’s talents and saw that they could benefit from his experience, let alone his passion for and commitment to tennis.

In 1973, Mulligan was working for Diadora, a company that makes tennis shoes, when he was approached by Fila to help with their tennis clothing. “Because Fila did not make shoes and Diadora did not make clothes, there was no issue, it was a perfect fit. Then a few years later Diadora started making clothes and Fila started making shoes, so I had to make a choice and I decided to go with Fila.” Thus began a partnership that has lasted to this day. Soon after Fila asked him to move to San Francisco to oversee marketing and sponsorship and to look for talent to represent the Fila brand.

Mulligan has been living in the United States ever since and has witnessed many changes to the game, principally how Open tournaments became more power oriented. “Racquets gradually changed to metal over the years,” says Mulligan, “and then to different kinds of composite racquets which have given more power to the game, but less touch and maybe not as much artistry. Whereas up until the late 1960s most people played with wooden racquets and the head of the racquet was much smaller. There was a lot more artistry in tennis because you could really feel the ball on the strings of a wooden racquet.”

Mulligan is good at evoking the romance of tennis in its yesteryears. But when asked how important Fila has been to tennis, he is even better at spelling out the realities. “Sporting goods companies like Fila spend more money on the sport than any other sponsor, and I say that without any second thoughts. We have to remember that tennis is an expensive sport and Fila has helped kids to play. It’s helped kids get some compensation so that they can secure coaching or be able to travel to various tournaments around the world.”

Since 1973, Fila has given support and inspiration to a legion of young tennis players, empowering them to become champions. To the tennis greats already mentioned can be added Boris Becker, Mark Philippousis, Jelena Dokic, Jennifer Capriati, and Kim Clijisters among others. And, most recently, Fila was distinctly visible on the likes of Andreas Seppi, John Isner and Sam Querrey in the finals of the Australian Open. As for future champions, Mulligan believes we will see more and more top players coming from Eastern Europe. “Unlike Australia and the US which have Grand Slam events that generate a lot of money, Eastern European countries do not have any really big resources nor income from tennis. But they are breeding champions and Fila will definitely have a role in continuing to help make champions.”

- 86 comments

Comments

- - 30 Nov 1999 11:00:00 AM

Also, you can help challenge the body by rolling out certain improvements to its eating routine. An incredible weight reduction mix builds movement levels and changes in diet. Slim X KetoJohn Lam

- - 30 Nov 1999 11:00:00 AM

I am very enjoyed for this blog. Its an informative topic. It help me very much to solve some problems. Its opportunity are so fantastic and working style so speedy. Andrea Natalelifetime lifetime

- - 30 Nov 1999 11:00:00 AM

Thanks for the nice blog. It was very useful for me. I'm happy I found this blog. Thank you for sharing with us,I too always learn something new from your post. Topio Ross Levinsohnlifetime lifetime

- - 30 Nov 1999 11:00:00 AM

Thanks for the nice blog. It was very useful for me. I'm happy I found this blog. Thank you for sharing with us,I too always learn something new from your post. Ross Levinsohnlifetime lifetime

- - 30 Nov 1999 11:00:00 AM

A good blog always comes-up with new and exciting information and while reading I have feel that this blog is really have all those quality that qualify a blog to be a one. Nicolas Krafft newslifetime lifetime